Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, which began on 24 February 2022, has been characterized by a flagrant disregard for civilian life and frequent war crimes. Russia has indiscriminately attacked Ukrainian cities, including with banned weapons, committed extrajudicial executions in areas under its control, and targeted clearly-marked civilian infrastructure in places like Mariupol. More than 13,000 civilians in Ukraine have been killed or injured – a number the United Nations says is likely an undercount – and millions have been forced from their homes.

Ukraine, where people over 60 years old make up nearly one-fourth of the population, is one of the “oldest” countries in the world. According to HelpAge International, the proportion of older people affected by the war in Ukraine is higher than that of any other ongoing conflict. This report shows how intersecting challenges, from disability to poverty to age discrimination, are compounded in emergency situations, putting older people at heightened risk.

Often reluctant or unable to flee their homes, older people appear to make up a disproportionate number of civilians remaining in areas of active hostilities, and as a result they face a greater likelihood of being killed or injured. Amnesty International documented several cases in which older people who stayed behind were hit by shelling or sheltered in harrowing conditions.

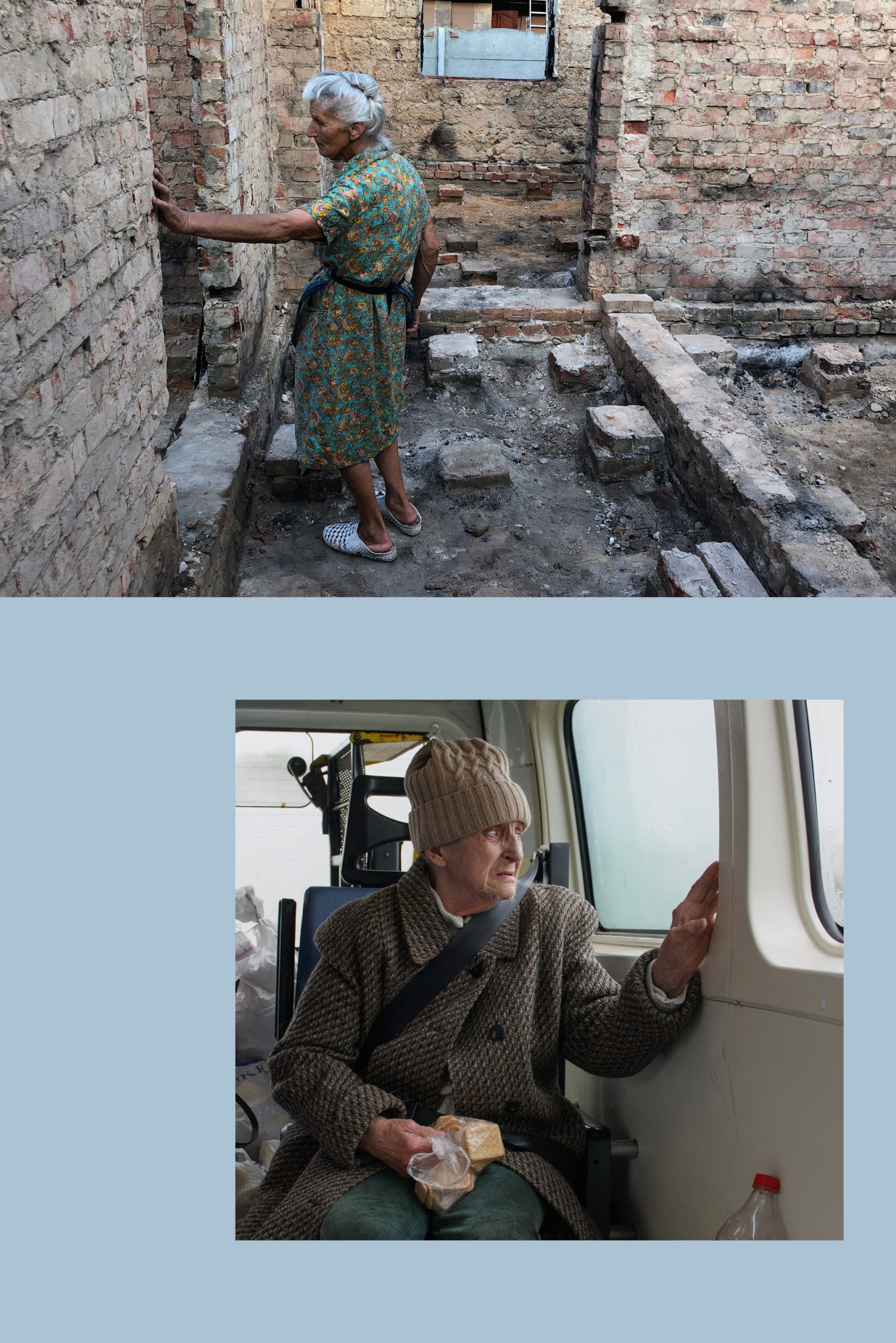

Even when they succeed in escaping such dangers, older people face distinct challenges in displacement. In particular, this report explores how the war has negatively impacted the rights of older people in Ukraine to adequate housing and to full inclusion and participation in their communities. Once displaced by the conflict, older people are often locked out of the rental market by pensions that are well below real subsistence levels, particularly since rental prices have increased at an alarming rate. Support for older people who have disabilities is rarely provided in temporary shelters. As a result, at least 4,000 older people have been given no option but to live in state institutions for older people and people with disabilities. While the goal of this policy is undoubtedly benevolent, it is in conflict with the rights of older people with disabilities, segregating them in isolated settings where they can be subject to abuse.

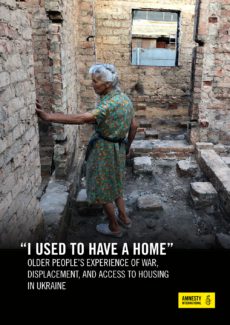

Those older people who remain in their homes in conflict-affected areas often do so because they have no alternative housing options or face greater difficulty evacuating. Many live in partially or fully destroyed housing that is dangerous to inhabit, lacking functional roofs, windows, electricity or heating, and without access to healthcare facilities, grocery stores or pharmacies. Information about evacuation plans, and evacuation routes themselves, are not always accessible to older people or adapted to their needs. In addition to the risk of being killed or injured, older people experienced health emergencies that went untreated as a result of staying in conflict-affected areas.

“Svitlana,” 64, who spent the first four months of the war in a Russian-occupied village near Kharkiv, said that her 61-year-old brother collapsed from a stroke in late April 2022. He was hospitalized, but the hospital did not have electricity or running water. He was discharged the next day: “They couldn’t do anything, they couldn’t do an electrocardiogram, they couldn’t do an encephalogram, they had no medications.” Less than a week later, Svitlana’s brother died from a second stroke, according to a death certificate seen by Amnesty International.

In total, Amnesty International interviewed 226 people for this report. Research was carried out between March and October 2022 and included a four-week trip to Ukraine in June and July 2022 as well as remote interviews. Amnesty International interviewed 87 older people living in shelters or in their homes, many of whom had health conditions or disabilities or were caring for those who did. Amnesty International also conducted seven in-person visits to state institutions, where many older people have been housed since the war began; delegates interviewed 106 people there, including staff and 83 residents, more than half of whom were over 60 years old. Finally, Amnesty International interviewed family members who had first-hand information about the situations of older people during the war, as well as advocates, volunteers, and those running shelters for the displaced.

Under international law, there is no specific definition of older age. While chronological age – such as 60 – is often used as a benchmark, this does not always reflect whether a person is exposed to risks commonly associated with older age. Amnesty International prefers a context-specific approach to older age, which takes into account the ways in which people are identified and self-identify in a given context, consistent with the approach taken by the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). In this report, most interviewees were over 60 years old, but several cases of people in their 50s who spoke of themselves as older people are also included.

Risk Factors in Displacement

According to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), nearly one-third of Ukrainians have been displaced by the conflict: 6.2 million people remain displaced within Ukraine, and 7.8 million are estimated to be refugees across Europe. According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), about half of internally displaced families have at least one member who is over 60 years old. While there is no reason to believe that older people have experienced more damage to their homes than other groups, many face several intersecting risk factors, including poverty, employment discrimination, disability and health conditions, that make accessing housing more challenging for them in displacement.

Older people are more likely than other groups to have a disability. In the European Union (EU), nearly half of people over 65 report difficulties with at least one personal care or household activity, and the numbers are higher among newer member states in eastern Europe. In Ukraine, more than half of those people registered as having a disability are of pension age.

Before the war, many older people with disabilities interviewed for this report had lived in apartments or homes that were adapted to their physical needs, such as with ramps or handrails. Older people with disabilities relied on formal and informal networks of family members, friends, neighbours, paid care workers or social workers to provide them the support they needed at home. Displacement shattered those support systems.

Before the war, “Nina,” who is 65 and uses a wheelchair, lived with her daughter, who also cannot walk, in Donetsk region. Her husband, who regularly travelled to Mariupol for seasonal construction work, paid a caretaker to support Nina and her daughter when he was away. At the start of the war, Nina’s husband was in Mariupol, and she had not heard from him since. In late May, with fighting approaching their city, the caretaker told Nina she was planning to flee, and would be unable to care for her anymore. Nina had no choice but to evacuate, and at the time of interview was living in one of the few temporary shelters accessible to people with disabilities in Dnipro. “I need a permanent home,” she said.

As my legs started getting weaker, I worried about staying there by myself.

Kateryna, 92-year-old

Kateryna, a 92-year-old from Kramatorsk with limited mobility, decided to stay in her home after her daughter, who lived in the same building and brought her food and other necessities, fled in mid-March. A male neighbour who was staying in the apartment building to look after his older father would bring her food, water, and blankets. But with her health declining, Kateryna worried about relying on him for more support.

“As my legs started getting weaker, I worried about staying there by myself,” Kateryna said. “If my legs totally refused me, what if I can’t go to the toilet by myself? Is [my neighbour] really going to clean me up? … It was getting so hard for me to stand, my legs were so swollen… I knew I needed to leave now.”

Because the shelter where she was staying in Dnipro had limited beds, Kateryna was sent to a state institution for older people in Rivne, in western Ukraine, with six other older women. She could not join her daughter, who had found an apartment in western Ukraine that was crowded and not accessible to someone with limited mobility.

Several older people said that before the war they received regular visits from social workers, who brought them groceries and medications, accompanied them to the doctor’s office, and helped them with light chores. While it is unclear how many social workers have fled conflict-affected areas during the war, interviews underscored that the disruption to such services was a key factor in some older people’s decision to leave their homes. The Ukrainian government has passed several decrees in an effort to secure the continuation of social services in conflict-affected areas, and says that 9,500 older people have received urgent at-home care during the war.

Poverty has posed additional risks to older people. Pensions in Ukraine are unsustainably low. While the real subsistence minimum for one person as calculated by the Ministry of Social Policy is 4,666 hryvnia (US$126) per month, pensions consistently fall well below that: about half of pensioners receive 3,000 hryvnia (US$82) or less per month. According to the Ukrainian Parliament Commissioner for Human Rights, nearly 80% of older people in Ukraine received pensions that put them below the poverty line before 2022.

Older women, who on average receive pensions that are 30% lower than men, typically as a result of shorter careers and time taken off due to caretaking responsibilities, are even more likely to face entrenched poverty. Women in Ukraine live 10 years longer than men on average, and older women interviewed for this report lived alone more frequently than older men.

Almost all older people interviewed for this report had owned their homes, which is a result of Ukraine’s privatization policies in the 1990s. Most would have been unable to afford to rent an apartment even before the war. But mass displacement has resulted in skyrocketing rents: in some western regions, rental prices have increased by 96 to 225%. Monthly support from the Ukrainian government and one-time payments by UN and other organizations have largely been inadequate to bridge the gap between extremely low pensions and high rental costs. Accessing financial support, which requires using an online app called Diya or requires in-person visits to various government offices, can prove challenging for some older people, who may not have a smartphone and who may have disabilities that make such in-person visits challenging without support.

At this age, it’s very hard to start from scratch.

Olena Nikitchenko, 59-year-old

Nina Silakova, 73, from Luhansk region, first lived in a school outside of Dnipro after her house was destroyed by shelling, likely by Russian forces, in March. In August 2022, the school required displaced people living there to leave ahead of the academic year. Nina, whose pension is 3,500 hryvnia (US$95) per month, verbally agreed to rent a part of a home in the same village for 1,800 hryvnia (US$48) per month plus utilities. But on 24 August, she had a heart attack. Her landlady evicted her because she feared having to care for Nina if her health worsened. Nina went to live with her 63-year-old sister, who had been renting a one-bedroom apartment for 3,500 hryvnia (US$95) in Kropyvnytskyi since March. But in October, the landlord, with whom they also had a verbal agreement, said he would evict them at the end of the month. Nina said: “Now there are no places for that price in the city because there are so many [displaced people]… I don’t know where to turn… Should I go out into the street, stand there and ask people? People will just pass by and think I am an ill old grandmother.”

Older people who were employed when the war started expressed concerns about finding work in displacement. Employment rates in Ukraine begin falling for those over 50 years old, and fall steeply after 60. In surveys, older people in Ukraine report being turned down for jobs on the basis of their age much more frequently than younger people. For many older people, the task of rebuilding careers or businesses in displacement has been a daunting one.

“At this age, it’s very hard to start from scratch,” said Olena Nikitchenko, 59, who had started a dental business in Mariupol after being displaced by the conflict in Donetsk in 2014. “When you’re 30 or 40 it’s easier, but for people our age we don’t even know how we are going to get jobs.”

One day [my husband] couldn’t feel his leg …The skin was peeling off. It looked dead… We brought him to the closest hospital. The doctors there said immediately that the leg had to be amputated.

Larysa, 65-year-old

The war and resulting living conditions undermined the health of older people, leaving them with disabilities and health conditions that further complicated their lives in displacement. Some were injured in attacks, overwhelmingly by Russian forces, while others lived in areas where they lacked access to medication or lived in unsanitary conditions. Health problems older people spoke about included untreated urinary tract infections, concussions or diminished hearing as a result of shockwaves and explosions, reduced mobility as a result of prolonged periods of isolation at home, and severe bronchitis and pneumonia after spending days without physical exercise in an unheated apartment without windows. In two cases, older men had their legs amputated because they did not have access to medication or sanitation during the war.

“One day [my husband] couldn’t feel his leg,” said Larysa, who was sheltering with her 67-year-old husband in a basement in Mariupol during the first month of the war. “I checked and it really looked awful. The skin was peeling off. It looked dead… We brought him to the closest hospital. The doctors there said immediately that the leg had to be amputated. He said the problem was gangrene.”

Amnesty International also interviewed five older people with psychosocial or intellectual disabilities who had lost their homes during the war: two were living in shelters, three in a psychiatric hospital. Amnesty International found that these and other older people with psychosocial or intellectual disabilities frequently struggled in displacement, as information on how to seek help was not accessible to them, and typically volunteers or shelter staff did not have the resources or skills to support them.

Rising Institutionalization

After older people were displaced from their homes, many struggled to find suitable accommodation. Pushed out of the private market by poverty, many older people turned to temporary shelters in schools, administrative buildings, train stations, former medical facilities, and sanitoriums. However, shelters were largely physically inaccessible to older people with disabilities and did not have staff with the capacity or skills to support people with disabilities. Sometimes, shelters said they could only take an older person with a disability if they were with somebody who could support them. Capacity at shelters that did have support services was extremely limited.

As a result, older people sometimes had no choice but to enter an institution for older people or people with disabilities after being displaced. Olha Volkova, who runs a physically accessible shelter in Dnipro, a hub for many people fleeing the war, estimated that 80% of the 926 people who had passed through her shelter as of early July were older people with disabilities. She said that due to a capacity of 170 beds and the lack of similarly-equipped shelters elsewhere, her organization often had no choice but to facilitate their transfer to an institution for older people or people with disabilities.

“About 60% of the people [get sent to institutions],” Olha said. “They can’t afford to rent housing, to pay for utilities, to eat. And so we have to send them to an institution.” Olha said her organization was able to facilitate some evacuations abroad of people with disabilities in the first month of the war, but that organizing the financing and logistics of such journeys largely fell on volunteer organizations like her own, making them a rare occurrence.

According to the Ukrainian Ministry of Social Policy, as of July 2022, more than 4,000 older people in Ukraine had been placed in state institutions in a simplified process after losing their homes. This does not include the number who may have been placed in private nursing homes or other types of facilities such as hospitals or psychiatric wards. Amnesty International interviewed 11 older people, both with and without disabilities, who had been institutionalized after losing their homes during the war, as well as 13 people in shelters who were about to be sent to an institution, often that same day, or were at risk of being institutionalized.

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), which both Russia and Ukraine have ratified, guarantees the full inclusion of people with disabilities, including older people with disabilities, in the community. While the goal of Ukraine’s policy to place older people in institutions is undoubtedly to provide them with urgently-needed shelter, food and warmth, according to the CRPD Committee this practice nonetheless violates the rights of people with disabilities, effectively segregating them in isolated settings where they are more at risk of neglect and abuse. Once placed in an institution, it can be very difficult – and sometimes impossible – for people with disabilities, including older people with disabilities, to leave. In a September 2022 report, the CRPD Committee expressed concern about the high rates of institutionalization in Ukraine and urged authorities there to “expedite deinstitutionalization of all persons with disabilities who remain in care institutions”.

We sit as if we are in the waiting hall of a train station… We are waiting for the end, what kind of end we don’t know.

Maryna, 75-year-old

Most older people who had been institutionalized since the war were adamant that living in an institution was not their choice. “Maryna,” 75, who was living in an institution for older people in Kharkiv region with her husband, said the couple were the last to flee the basement of their nine-story apartment building. When they were evacuated, they were not offered any accommodation but the institution, even though neither had a disability and both had lived fully independent lives before the war.

“I want to live at home, where I can go out whenever I want, without control. Here you need permission to go out,” Maryna said. “We sit as if we are in the waiting hall of a train station… We are waiting for the end, what kind of end we don’t know… We are despondent with uncertainty.”

Nina, 70, had to be hospitalized for severe bronchitis and pneumonia after fleeing her home in Sieverodonetsk, where she was finally rescued after spending 10 days alone in her apartment in below-freezing temperatures. She was told by staff at the shelter where she was staying that she would most likely be sent to an institution.

“Why should I go to a nursing home? I had my own home, it was totally equipped to my needs… I could happily live on my own,” she said. “Why do I need to go to a nursing home when I can do everything for myself?”

Lying down all day is not a life.

Halyna Dmitriieva, Wheelchair user

Some worried about the conditions in institutions once they arrived there. Halyna Dmitriieva, 51, whose main caretaker is her 85-year-old aunt, has cerebral palsy and uses a wheelchair. She worried about the impact that life in an institution would have on her health.

“They [shelter staff] say we’ll be sent to a nursing home,” she said. “I have a lot of friends with cerebral palsy, they have ended up in institutions and they have told me about it. I know that there won’t be staff who will lift me up and put me in the wheelchair every day, that I will spend all my time in bed, I will get bedsores… Lying down all day is not a life.”

Halyna’s concerns are justified: Amnesty International visited seven state institutions for older people and people with disabilities in Ukraine. While this report is not meant to provide a comprehensive account of conditions in institutions, Amnesty International found several disconcerting trends, including neglect, isolation, and restrictions on freedom of movement. In one institution, residents reported physical abuse.

Neglect in institutions was particularly acute for residents with limited mobility. They were almost never moved from their beds or provided with any kind of support or engagement beyond feeding and basic sanitation. This often appeared to be because there were simply not enough staff to care for residents, as typically three or four caretakers provided support to groups of 30 or 40 residents. The National Preventive Mechanism (NPM) of Ukraine, whose monitors can visit places of deprivation of liberty including institutions, said in its 2020 annual report that 99% of residents with limited mobility were denied the opportunity to take walks outside.

“In an institution there is basically no rehabilitation,” said Olha Volkova, who runs an accessible shelter in Dnipro. “A person will lie down until they die.”

Given these conditions, and the fact that, as concluded by the CRPD Committee, institutionalization inherently violates the rights of people with disabilities, it is of utmost importance that the Ukrainian government monitor the situation of people placed there, and ensure they have access to alternative housing as soon as it becomes available.

This issue is particularly urgent given the risks that people with disabilities may end up trapped in institutions. For example, “Vira,” 82, who had been admitted to an institution for older people after being hospitalized for pneumonia in February 2022, said that she had been sent there after her grandson told the doctors he was not willing to care for her anymore. “I do not agree [with this decision]. Nobody asked me,” she said. She described the challenges of leaving: “They told me if I didn’t like it, I can go home. And here I don’t know the director. I don’t know the doctors. In general, I never leave this floor.”

While Amnesty International delegates were unable to travel to Russia or Russian-occupied parts of Ukraine because the Russian authorities severely restrict access to international human rights organizations, delegates documented several cases of older people in those areas being institutionalized. This raises concerns about the scale of this issue in Russia or Russian-occupied areas, particularly as institutionalization makes it more difficult for older people there to reunite with family members or to leave Russia.

Living in Dangerous Conditions, Destroyed Housing

Many older people have not fled: sometimes because they were reluctant to abandon their homes, sometimes because they did not know where else to go, and sometimes because evacuation routes were not accessible to them. As a result, older people appear to make up a disproportionate number of people remaining in some of the most conflict-affected parts of Ukraine, posing risks to their safety and health.

According to OHCHR, which collects information on civilian casualties in Ukraine, older people make up a disproportionate number of civilian deaths and injuries in the war: in cases where the age of a victim was recorded, people over 60 years old made up 34% of people killed and 28% of people injured from February to September 2022, as well as around 30% of total civilian casualties in the 2014-2021 war. People over 60 make up 23% of Ukraine’s population.

Amnesty International documented several cases in which older people who stayed behind were killed or injured in the hostilities. Mykola Trukhan, 86, decided to stay in his home in Hostomel, Kyiv region, after the rest of his family fled on 11 March 2022. His niece, Lidiya Yarosh, said: “My mother-in-law ran to him when we were evacuating… She tried to convince him to leave, but he said, ‘No, I’m not going to leave, I don’t want to leave my dog and my home.’” Mykola was killed a few days later, when a shell landed on his house, neighbours told Lidiya.

For others, staying in conflict-affected areas meant regular close misses. Amnesty International spoke to several older people whose apartments had been directly impacted by shrapnel from nearby explosions. After a cluster munition fired by Russian forces sent fragmentation flying into their ground-floor apartment, one older couple in Kharkiv described sleeping for several months in their bathroom, with a board placed over the bathtub, as it was the only windowless room in the house.

Older people sometimes stayed in areas under Russian occupation, often for reasons including family connections and concerns about losing property. Some sources suggest older people stay behind in larger numbers than other groups: in Mariupol, for example, city officials said the percentage of pensioners as part of the city’s population ha doubled since the war began. Under international law, Russia, as the occupying power in these regions, has an obligation to ensure the maintenance of medical services, hospitals, public health and hygiene.

This demographic imbalance in occupied areas is particularly problematic given that Russia has continued to prevent the access of humanitarian aid to those areas, in flagrant violation of international law. Interviewees told Amnesty International that there were dire shortages of medications and, in some areas, few functioning health facilities. This is of particular concern to older people, who are more likely to have health conditions.

Other older people stayed in homes that, due to damage from the war, did not have roofs or windows to protect them from weather conditions. While some older people received support from volunteers or local authorities to do repairs, there is currently no legal mechanism in Ukraine for providing people compensation for property destruction or damage. It is unclear how most older people in such situations, who almost invariably could not afford to pay for repairs themselves, will survive the winter conditions.

Amnesty International also interviewed older people living in areas without electricity, water, heating, or access to grocery stores and pharmacies. “Mykola,” 63, who lives in the Saltivka neighbourhood of northern Kharkiv, said he was the only person living in the 40 units in his block of flats. “We haven’t had electricity, gas, or water from the first days of the war,” he said. “It’s hard to wait in lines for aid, the lines are very long, I usually spend two to three hours per day in the line… There are no shops in my neighbourhood to buy food.”

While many older people chose not to leave their homes, some older people said they had wanted to leave, but that evacuations were not physically accessible to them, or information was distributed in ways that excluded them.

Nobody told us about evacuations, I always found out only afterwards.

Liudmyla Zhernosek, 61-year-old

Liudmyla Zhernosek, 61, who lived in Chernihiv with her 66-year-old husband, who is an amputee and uses a wheelchair, said: “I saw every day younger people walking alongside my building with backpacks on. Only later I found out from others in the stairwell that they were going to the centre of the city, there were still evacuations from there. But that would have been 40 minutes on foot, I couldn’t get there with my husband. Nobody told us about evacuations, I always found out only afterwards.”

The challenge of evacuating was particularly acute for older people in cases where more than one family member had a disability. “Leonid,” who is 76 and blind and lives with his wife, who cannot walk due to a stroke, said: “It’s one thing just to be blind. You can take a person by the arm and lead them. For me, I also need to bring [my wife]. In evacuations they don’t give you any kind of accompaniment.”

The Way Forward

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which has had a devastating impact on civilians of all ages, threatens the physical security of older people and has forced millions of them from their homes. Ultimately, the most expedient way to protect the rights of older civilians in Ukraine is for Russia to end its unlawful war.

But older people in Ukraine faced numerous issues that placed them at risk before the war, from disability to poverty to age discrimination. The war has only amplified those vulnerabilities, making it effectively impossible for many of them to access safe and accessible housing. Older people are locked out of the private rental market by poverty-level pensions, unable to live in temporary shelters if they have disabilities, and are forced into institutional settings that violate their rights. It should be no surprise that in such circumstances, many older people choose to stay behind in homes that are in dangerous areas, lack functional roofs or windows, or do not have electricity, heat, or running water.

The Ukrainian government has made significant efforts to evacuate people from conflict-affected areas, including by announcing the mandatory evacuation of around 200,000 people from Donetsk region ahead of the winter. These are important efforts which may save the lives of many older people. However, it is clear that once in displacement, older people are often stranded without access to adequate housing. Support for older people, particularly those with disabilities, should not end with evacuation: older people must be offered support and safe, accessible accommodation in non-institutional settings on a priority basis.

The cost and logistics of ensuring housing for older people displaced by the war should not be Ukraine’s alone. Other countries should facilitate the evacuation of older people, with special attention paid to older people with disabilities, to accessible accommodation abroad where possible. International organizations, partner nations and non-governmental organizations should do more to financially support older people so that they can afford to rent homes, and, working together with the Ukrainian authorities, include them among those prioritized for placement in any newly-built accommodation.

At present, there is no global treaty on the rights of older people. The findings in this report clearly show that older people have intersecting identities, which taken together put them at heightened risk during an emergency. So far, older people’s rights are protected by a patchwork of international treaties that are universal in scope or pertain to other groups. But existing law provides inadequate protection, and has done little to increase the visibility of human rights abuses against older people.

The war in Ukraine must serve as a wakeup call for the international community. Only an international convention specific to older people can truly safeguard their rights.